“Eric Gill sees in this industrial dismemberment of labor a crucial distinction between making and doing, and he describes ‘the degradation of the mind’ that is the result of the shift from making to doing. This degradation of the mind cannot, of course, be without consequences. One obvious consequence is the degradation of products. When workers’ minds are degraded by loss of responsibility for what is being made, they cannot use judgment; they have no use for their critical faculties; they have no occasions for the exercise of workmanship, of workmanly pride. And the consumer is degraded by loss of opportunity for qualitative choice. This is why we must now buy our clothes and immediately re-sew the buttons; it is why our expensive purchases quickly become junk.

With industrialization has come a general depreciation of work. As the pice of work has gone up, the value of it has gone down, until it is now so depressed that people simply do not want to do it anymore. We can say without exaggeration that the present national ambition of the United States is unemployment. People live for quitting time, for weekends, for vacations and for retirement; moreover, this ambition seems to be classless, as true in the executive suites as on the assembly lines. One works not because the work is necessary, valuable, useful to a desirable end, or because one loves to do it, but only to be able to quit — a condition that a saner time would regard as infernal, a condemnation. This is explained, of course, by the dullness of the work, by the loss of responsibility for, or credit for, or knowledge of the thing made. What can be the status of the working small farmer in a nation whose motto is a sigh of relief: “Thank God it’s Friday”?

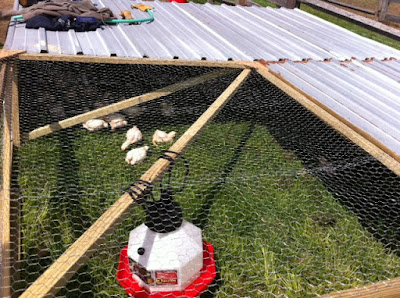

But there is an even more important consequence: By the dismemberment of work, by the degradation of our minds as workers, we are denied our highest calling, for, as Gill says, ‘every man is called to give love to the work of his hands. Every man is called to be an artist’ (Gill, A Holy Condition of Working). The small family farm is one of the last places — they are getting rarer every day — where men and women (and girls and boys, too) can answer that call to be an artist, to learn to give love to the work of their hands. It is one of the last places where the maker — and some farmers sill do talk about ‘making the crops’ — is responsible, from start to finish, for the thing made. This certainly has a spiritual value, but it is not for that reason an impractical or uneconomic one. In fact, from the exercise of this responsibility, this giving of love to the work of the hands, the farmer, the farm, the consumer, and the nation all stand to gain in the most practical was: They gain the means of life, the goodness of food, and the longevity and dependability of the sources of food, both natural and cultural. The proper answer to the spiritual calling becomes, in turn, the proper fulfillment of physical need.”

– Wendell Berry, A Defense of the Family Farm